The Constitutional Court's Efficiency: An Update from 2022 to 2024

Picture Credit: "Constitutional Court, Johannesburg, South Africa" by fromagie is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

South Africa's apex court is slower than it has ever been. Our new data shows the problem is getting worse, not better.

In 2022, we published a study showing that the Constitutional Court of South Africa had a serious efficiency problem. Between 2010 and 2021, the average time the Court took to hand down a judgment after hearing a case had almost exactly doubled. Our findings contributed to growing public concern about the internal operations of our apex court. Media commentators, public interest organisations, and even the judiciary’s own leadership began openly confronting the Court's difficulties.

Three years later, we've updated our study. The full results will soon appear in volume 15 of the Constitutional Court Review. As they show, the overall picture remains troubling. The Court has not resolved its efficiency problems. In important respects, they have become worse.

The Core Finding: Still Slowing Down

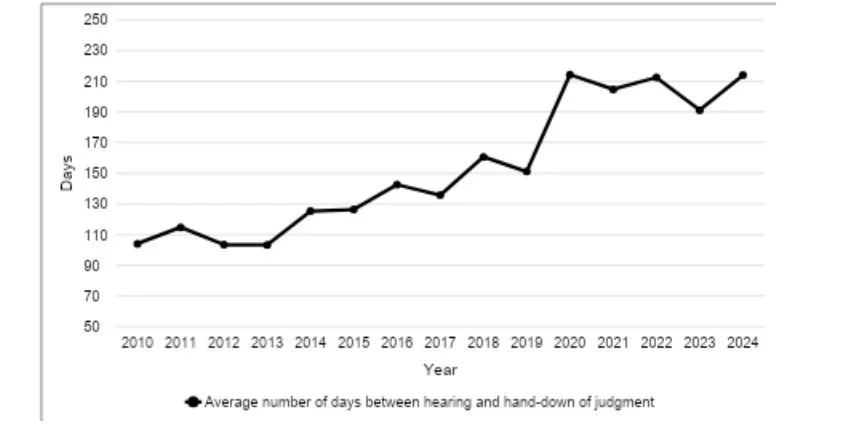

Our headline finding is simple but stark. In 2024, the Constitutional Court took an average of 214 days—over seven months—to hand down a judgment after hearing a case. This matched 2020 as the Court’s slowest year in our entire 15-year period of study.

To put this in perspective: in 2010, the Court was handing down judgments in an average of 104 days—just over three months. By 2024, that figure had more than doubled.

Average number of days between hearing and hand-down, 2010–24

What's Driving the Problem?

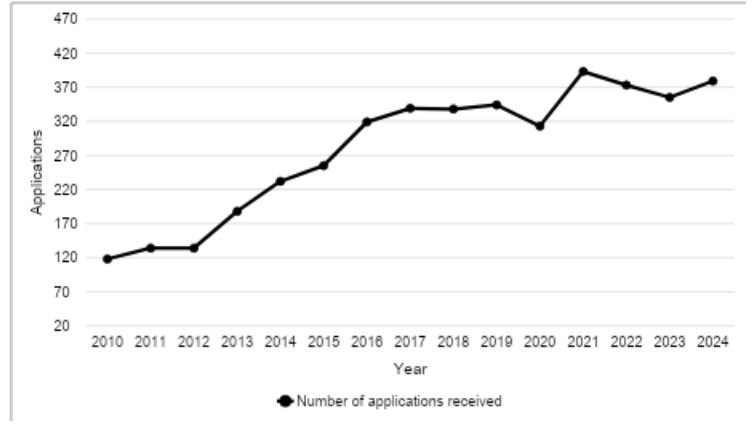

The easy explanation would be workload. The Court is receiving far more applications than it did 15 years ago. In 2010, the Court received 118 new applications. By 2021, that number had jumped to 393.

Number of new applications filed, 2010–24

There has undoubtedly been an increase in the Court’s workload over the last 15 years. This is usually attributed to the expansion of the Court's jurisdiction in 2013 to include non-constitutional matters.

But we doubt this adequately explains the Court’s efficiency problems. The full story is more complicated—and more troubling.

While new applications filed with the Court remain high, they have in fact plateaued in recent years. In addition (and this point is not evident from the above graph), the Court is hearing fewer of those applications than it did before. In 2024, the Court handed down fewer reasoned judgments than in any year since 2012 (excluding the Covid-disrupted year of 2020).

In other words, the Court’s workload is no longer increasing, and by some metrics may even be decreasing—yet it is taking longer than ever to complete it.

As we have been arguing since 2022, there is a deeper cause contributing to the Court’s woes. This is its diminished judicial capacity. Put simply: fewer judges are doing the work.

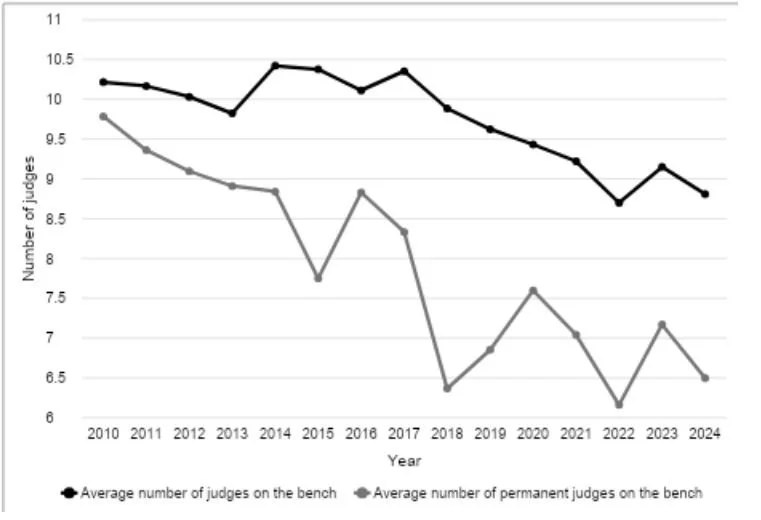

Though the Constitution provides that all 11 of the Court’s judges will sit on every case, it now routinely sits with only eight or nine. Since 2010, the Court has “lost” 3.3 notional permanent judges from the average case.

Size and composition of the bench versus hand-down time, 2010–24

There are a few inter-related reasons for this troubling loss of human resources.

First, several vacancies on the Court have remained unfilled for years, primarily because of the halting and notoriously unprofessional recruitment processes of the Judicial Service Commission. Strikingly, one vacancy that fell open in October 2021 still has not been filled.

True, the many gaps among the Court’s permanent staff have been plugged with acting judges (which explains the upper line on our graph). But this creates its own problems. Acting judges, typically appointed for three- or six-month stints on the Court, might take a while to get up to speed, and often end up writing most of their judgments after returning to full-time responsibilities elsewhere, which likely slows things down.

Finally, both Chief Justices Zondo and Maya have been frequently absent from hearings, diverted by the leadership demands of their role.

“Delays at the Constitutional Court are not just statistics. They represent justice deferred for actual people—families waiting to know their rights, businesses in legal limbo, public interest cases held in abeyance.”

The Bigger Picture: A Court in Crisis?

Unfortunately, the Court’s administrative problems appear to go deeper than just slow judgment hand-down times. Our research has uncovered several other concerning trends.

First, there is a backlog of new applications awaiting processing. At the end of 2024, the Court had 309 pending applications. Over half had been waiting for directions for more than six months; nearly a third had been stagnant for over a year. In 2012, by comparison, the average time the Court took to determine an application of this kind was just 33 days.

Second, the Court's record-keeping has deteriorated. Case files are incomplete and online records contain errors. Tracking even very basic information has become difficult. This isn't just an administrative inconvenience: without reliable data, even the Court itself cannot properly assess its functioning or measure whether reforms are working.

Third, the Court has started taking some concerning shortcuts. It now decides cases without hearings, issues summary dismissals, and in one matter even produced a paragraph-long "dissent" appended to its order, instead of a full reasoned opinion. These practices, though understandable given the pressures on its capacities, make the Court's work less transparent. They also do not get at the root of the problem.

What Needs to Change?

The most obvious remedial measure is to fill the Court's vacancies with capable and hard-working judges. This means the Judicial Service Commission must conduct interviews more expeditiously and professionally, encouraging rather than deterring qualified candidates from applying.

Beyond that, the Court may need to rethink its role. Should it try to hear every appeal where it believes the lower courts have made an error? Or should it focus on the relatively small number of cases that genuinely raise major constitutional issues or have wide legal impact?

The former approach has its advantages. But we believe the latter approach is more appropriate for an apex court—and it may be the only approach that is sustainable.

The Court has broad discretion in deciding which cases to hear. It should use that discretion more deliberately: setting clearer standards for which cases merit its attention, being more selective about subject areas where specialist tribunals exist, and perhaps imposing costs orders on frivolous appeals.

More dramatic reforms are also on the table. Chief Justice Maya has, in the past, proposed that the Court should be allowed to sit in panels, or that it should simply be merged with the Supreme Court of Appeal. These are major structural changes to our judiciary. They should not be undertaken lightly.

Why This Matters

Delays at the Constitutional Court are not just statistics. They represent justice deferred for actual people—families waiting to know their rights, businesses in legal limbo, public interest cases held in abeyance. As the old saying goes, justice delayed is justice denied.

Incidentally, although it was not possible to cover 2025 in our full study, we can now see that the Court’s performance became even worse last year: its average hand-down time, according to our back-of-the-envelope calculations, was about 245 days. Its longest hand-down time — in Godloza v S, in which two accused persons sought to appeal their convictions— was an astonishing 608 days.

This confirms that the Court's efficiency problems, which we first identified in 2022, have not been resolved. Indeed, they seem now to be worse than ever. The Court's leadership has acknowledged these challenges openly, which is commendable. Now the hard work of fixing them must begin in earnest.

Leo Boonzaier is an Associate Professor in the Department of Private Law at Stellenbosch University. Nurina Ally is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Public Law at the University of Cape Town and the Director of the Centre for Law and Society. Their full article will appear in Constitutional Court Review Volume 15 (2025).