Thirty-Five Years Later: Why Namibia Must Now Choose Ubuntu’s Soul

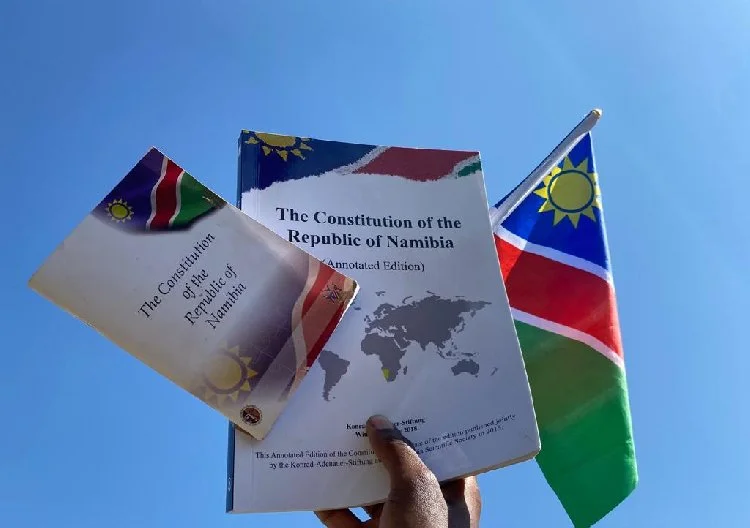

Picture Credit: Namibia Today

Death and democracy dance together in Namibia’s constitutional watershed moment. The passing of Founding President Dr. Sam Nujoma on February 8th this year occurred, with pregnant symbolic resonance, a mere hours before Constitution Day.

This is what three colleagues and I noted as our School of Law at the University of Namibia convened jointly with the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung a conference to celebrate and contemplate the 35th anniversary of the Namibian Constitution. Entitled “Between Legacy and Lodestone”, the conference that took place in August offered a time for what I term “forward-looking soul-searching.”

This coincidence invites us to ask: What futures can emerge from the magnetism of loss and law, memory and metamorphosis? In this piece, I sketch one such future – where the current liberal Bill of Rights in Namibia’s constitution and constitutionalism is replaced by a decolonial Bill of Rights. But, before we envision together such a future, I first look back at the road travelled so far in the next section.

Achievements Against the Odds

Namibia’s Constitution has survived 35 years—a feat both ordinary and extraordinary. Ordinary because constitutions should endure; extraordinary because in Africa, they rarely do. The data speaks volumes: while constitutions average 19 years worldwide, African constitutions last only 10.

Even when approached through the seemingly neutral lens of the age of national constitutions in force today across the continent, Namibia’s accomplishment eclipses statistical outliers. Based solely on their dates of promulgation, my own calculations reveal that the average age of a national constitution in Africa stands at approximately 25.15 years. Namibia’s fundamental law, however, exceeds this continental benchmark by a decade.

This gap represents more than a chronological anomaly; it manifests as a testament to the ability of institutions to survive in a region where constitutional mortality has become the norm rather than the exception. The decade-long surplus speaks to something deeper than durability—it signals a constitutional ecosystem that has successfully navigated the treacherous tides of post-colonial governance and maintained its foundational integrity.

Within the ecology of Africa’s 54 recognized states, Namibia’s constitutional longevity finds itself in remarkably select company. Only four constitutions predate Namibia’s: Botswana’s charter since 1966 (now 59 years), Mauritius’s post-independence constitution from 1968 (57 years), Tanzania’s socialist-influenced document from 1977 (48 years), and Liberia’s post-conflict constitution from 1986 (39 years). This exclusive quintet represents a mere 9% of the continent’s constitutions—a statistic that underscores the extraordinary nature of constitutional survival in African political contexts.

The philosophical implications of this quintet extend beyond temporal coincidence into the realm of democratic theory and practice. What unites the 1990 Namibian Constitution with its four predecessors is their shared commitment to democracy—a correlation that suggests profound interconnections between constitutional longevity and political openness. Freedom House’s latest rankings illuminate this relationship: The older half of Namibia’s predecessors, Botswana and Mauritius, earn the designation of “free” societies while the non-government organization (NGO) classifies Liberia as “partially free.”

Though Freedom House describes Tanzania as “not free”, this gradient across constitutional age nonetheless induces a compelling hypothesis: the older the national constitution, the more robust the democratic foundations. This pattern reveals a molecular truth about the symbiosis between constitutional durability and democratic maturation—where time becomes both the crucible and the reward of genuine democratic commitment.

“The liberal paradigm in Namibia has secured rights but not redistribution, freedom but not flourishing, democracy but not dignity.”

The Supreme Court, which performs higher than the global average in terms of judicial independence and effectiveness, has achieved notable landmarks in interpreting the Efinamhango.[i] Notably, as Mahomed AJ famously observed in S v Acheson (1991), the Constitution serves as “a mirror reflecting the national soul”, recognizing that constitutional interpretation must embody the deepest aspirations and values of the Namibian people. Next, the Mwilima case (2002) established the principle that the right to legal representation transcends political allegiances, with the Supreme Court obliging the state to provide legal aid even to those accused of attempting to secede the Caprivi Region (now Zambezi Region) from the Republic.

Third, the Swartbooi case (2021) refined the doctrine of separation of powers by holding that the Speaker of Parliament had overstepped his constitutional authority in indefinitely suspending opposition members of Parliament for disruptive behavior. Finally, the Haufiku case (2019) delicately balanced national security imperatives and press freedom, ruling that intelligence services cannot invoke security concerns as blanket justification for suppressing journalistic inquiry. In ranking Namibia as the country with the continent’s greatest press freedom in 2021, Reporters Without Borders explicitly mentioned the Haufiku ruling.

Moreover, the past 35 years have been marked by peaceful transitions of power—from Nujoma to Hifikepunye Pohamba (2005), Pohamba to Hage Geingob (2015), and now Geingob to Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah, the first female President of Namibia.

Nevertheless, these achievements should not mask deeper wounds and a constellation of fault lines. The Constitution has presided over a series of back-to-back economic crises since 2016 and over Namibia becoming the world’s second-most unequal society. More than a million—one-third of the population—inhabit informal settlements. The Fishrot scandal, the SME Bank collapse, and the highest unemployment in Southern Africa, including youth unemployment at 44.4%, have further deepened disillusionment. Most devastatingly, Namibia carries the somber distinction of recording Africa’s highest suicide rates.

These are not just failures of constitutionalism; they are failures of liberalism. The liberal paradigm in Namibia has secured rights but not redistribution, freedom but not flourishing, democracy but not dignity.

Toward a Decolonial Bill of Rights: Ubuntu Against Liberalism

I propose a decolonial Bill of Rights grounded in Ubuntu rather than liberalism. A decolonial Bill of Rights would reconceptualize four fundamentals. First, property: understood as communal trusteeship, not solely as individual possession. Land would belong to ancestors, present generations, and the unborn—making speculation impossible, redistribution inevitable. Second, personhood: conceived as interconnected beings, not as atomized individuals. As articulated in the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, this personhood also enshrines duties and peoples’ rights alongside the traditional rights to embrace indigenous and marginalized communities beyond individualistic vocabularies.

Third, governance: defined not as representative democracy but as participatory consensus. Fourth, efficiency: anchored in adevelopmental-state philosophy as opposed to the current “mixed-economy” neoliberalism.

Critics will retort that such transformation risks dismantling the very longevity that distinguishes Namibia’s Efinamhango among African nations. In fact, Namibia’s political culture accounts for the endurance of its Constitution more than the inverse.

Liberals will cry: “Impractical! Romantic! Anti-modern!” However, modernity has given us inequality, individualism has birthed isolation, practicality has produced poverty.

The liberal objection—that individual rights protect against tyranny—misunderstands the nature of tyranny in this part of the world. Our despots weaponize liberalism: property rights to dispossess, free speech to divide, electoral democracy to legitimate autocracy. By contrast, Ubuntu’s consensus-building, its emphasis on restoration over punishment, and its integration of individual and collective offer better bulwarks against both tyranny and chaos.

Conclusion: The Next Half-Century

Namibia stands at a crossroads. One path continues liberalism’s failed experiment: another ventures toward decolonial possibilities. The choice is not between tradition and modernity but between imposed universalism and grounded pluriversalism. Forward-looking soul-searching demands we choose courageously.

.

[i] ‘Efinamhango’ means ‘the Constitution’ in Oshiwambo.